ICONIC PORTRAITS : The Who’s Who of Arnaud Baumann

Who’s Who is the directory of people who are supposed to be important in the life of a country. The first English edition dates from 1849, the French from 1953. Arnaud Baumann’s more recent, fresher, more unbuttoned Who’s Who began in the ’80s, when as a young photographer, he began to frame in his viewfinder people who mattered, particularly to him. For example, the libertarian squad of the newspaper Hara-Kiri, of which there remains a spirit, a disruptive and ill-bred body of work, a legacy, an offspring, a tragedy – the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January 2015 – and a book-bible, Dans le ventre de Hara Kiri (Éd. La Martinière, 2015), a tumultuous echography produced by Arnaud Baumann with his long-time alter ego, photographer Xavier Lambours. The difference between the ordinary Who’s Who and his is that in his it’s the texts that are brief and secondary, and the photos that are large and important.

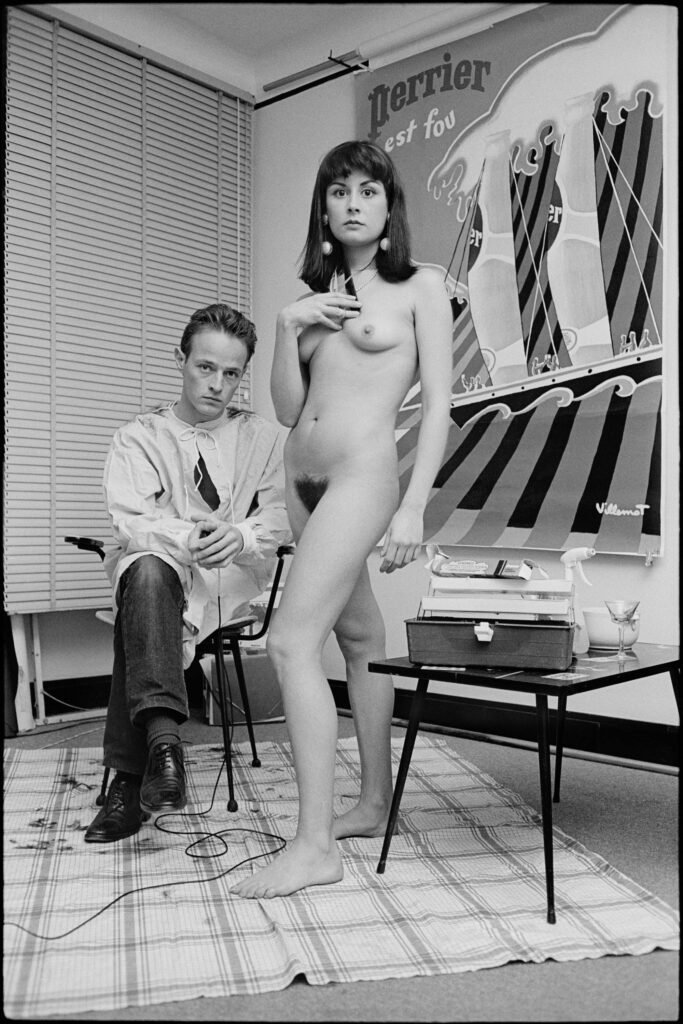

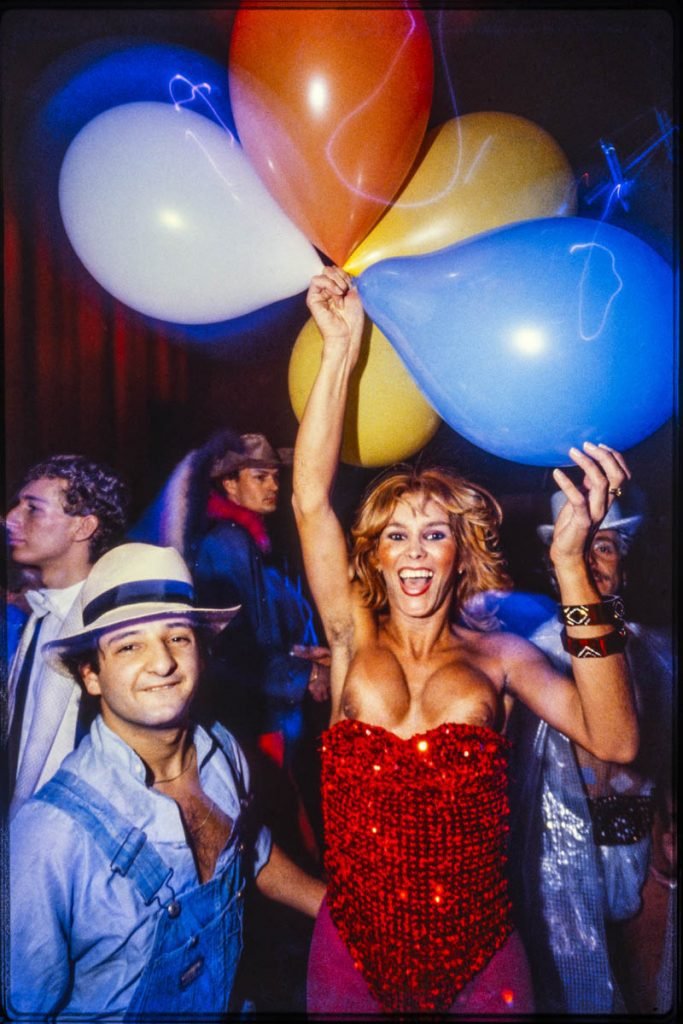

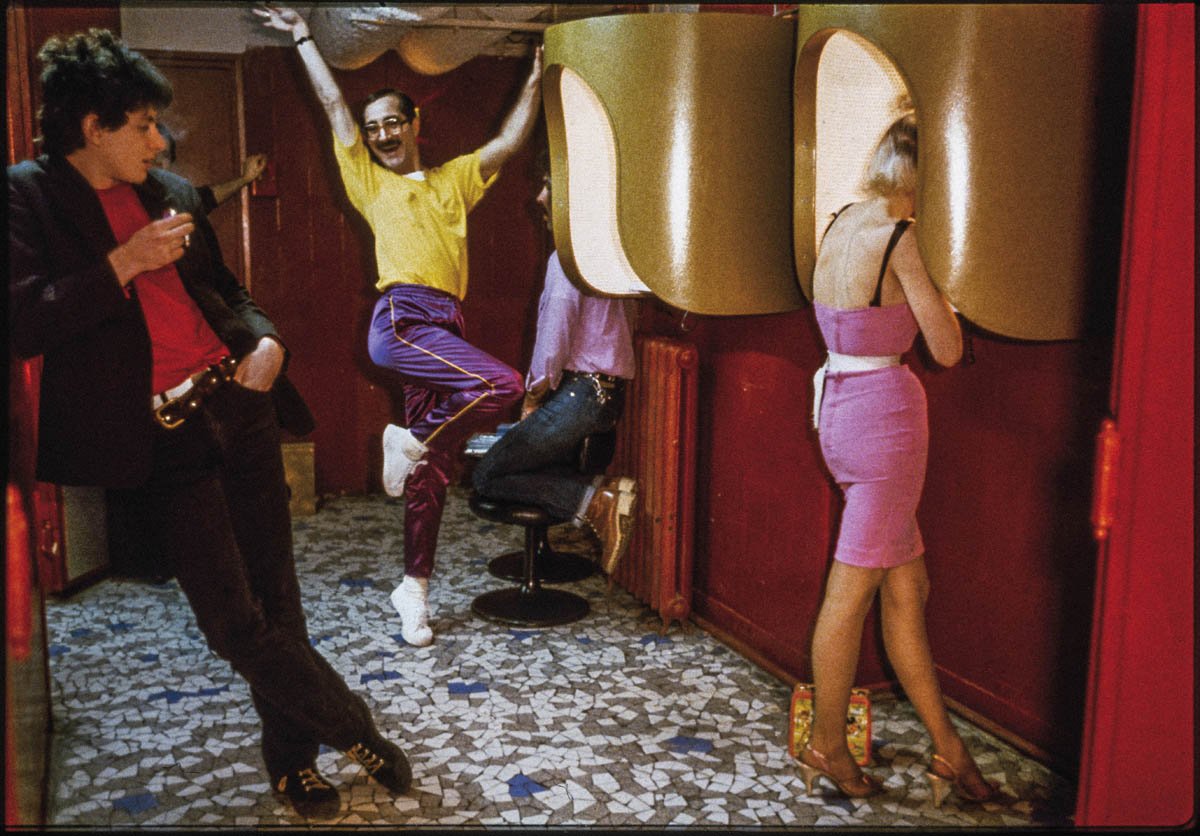

If one of his predilections as an artist is portraiture, his favorite exercise, his originality, his great success, his stylistic signature, is the happy portrait. To a large extent, Iconic portraits is an exhibition – and a collector’s book (limited to 100 copies) – about mischief and irony, euphoria and joy, humor, jokes, mischief and self-mockery, which is to derision what self-criticism is to criticism: progress. More than a Who’s Who, it’s a gallery of tableaux-cabrioles, exaggerated mimics, pasquinades, as we used to say in Victor Hugo, stretching from the end of the xxᵉ century to the beginning of the xxiᵉ, while we wait for the rest, because a century is a long time. Even more than a yearbook, it’s a kind of Légende dorée in images, secular, profane, cheerfully pagan, if you leave out Abbé Pierre, Julien Green and a few emeritus heads. More than a golden legend, it’s a multicolored dictionary of biographies written on silver film, from Leica to Polaroid camera. Nostalgic readers will see it as an affectionate, droll, effervescent, Dionysian and sometimes sulphurous repertory – but this sulphur smells of humanity – of a host of milieus and periods that make up a demography of preferences, a selective sociology and, in short, the chosen inventory of a memorialist multiplied in fifteen worlds.

In the end, we find dozens of old acquaintances who, on screens, stages, newspapers, books, art galleries and museums, have accompanied us through our successive ages, and who are a bit like relatives we’ve known, if not in the world, at least in the spectacle of the world, a substitute phantasmagoria in which we undoubtedly live more than in reality. And if many of these long-lost acquaintances have disappeared, most of them, at the time of these portraits, are the embodiment of that kind of happiness of being and vitality of group or couple that radiates from the image when the happiness of being and vitality of the subjects are redoubled by those of the portraitist. A photographer’s portraits, in fact, are also the photographer’s portrait, and each of them, when the subject, photographer and portrait are up to scratch, makes a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

The atmosphere, precisely, is one of celebration, of rest from toil. But from time to time, you need to take a break from rest, not so much from work as from seriousness, anxiety and danger. This is what happens here, without the photographer deviating much from the measured baroque or youthful naturalness that he conveys from the first of his images to the last.

Emil Cioran, tucked away in his attic in the Latin Quarter, a figure of defeated dough, raised towards a skylight he would like to open, or close. Hair as thick as anguish. The face of an abused old child, overwhelmed, slapped in the face by the nasty rectangular light of a Heaven where the persecuting demiurge of the Gnostics has shamelessly taken up residence. Photogeny of the inconsolable. Look no further for a better illustration of disappointed mysticism.

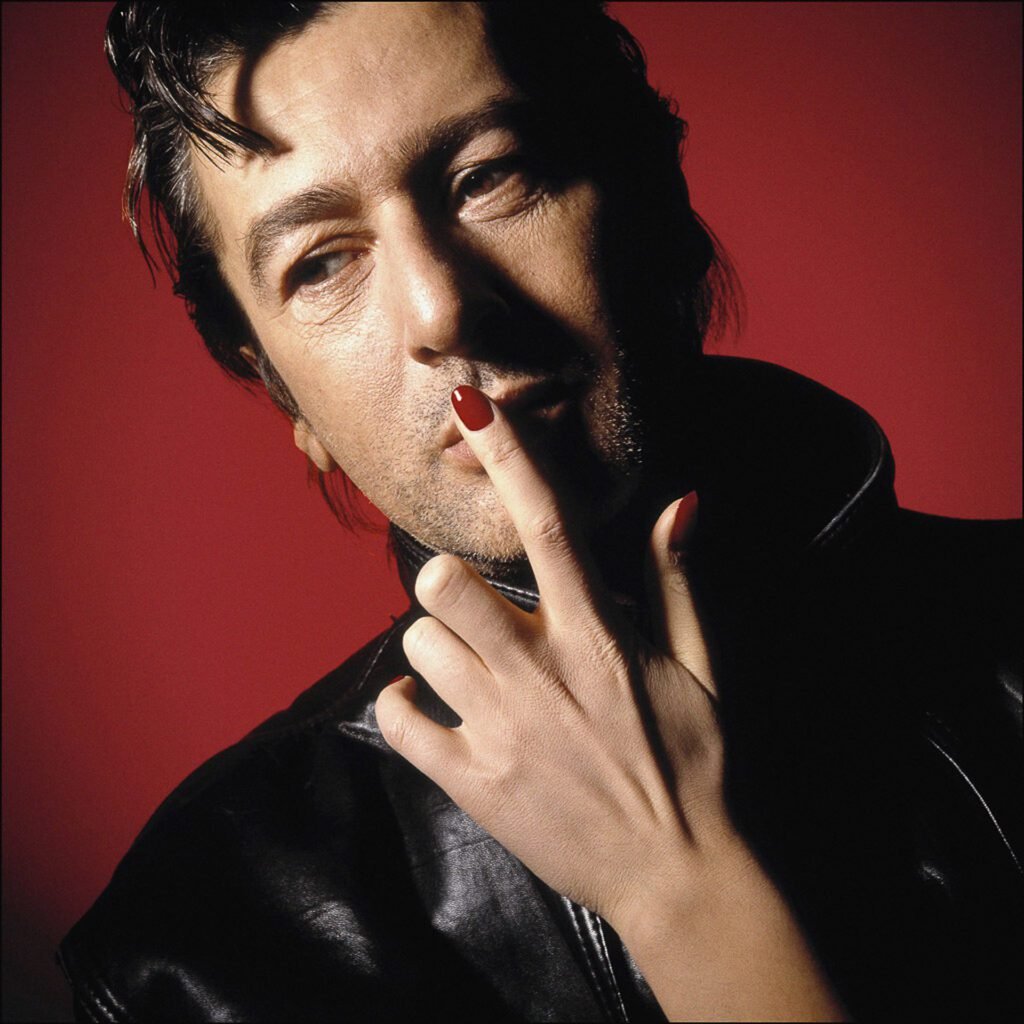

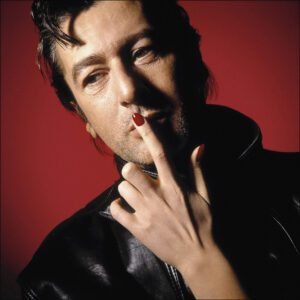

Bashung, for instance. That stork finger on his lips. This finger of finesse with a scarlet nail. That finger that isn’t his, but which suits him so well… The finger of his feminine side, since they say you have to have sides, like with cakes? A queen of hearts? An adorer? Of modesty? Delicacy? Melancholy? Of death? Louis XIII, secret king, dies with an identical gesture or pose, but it was his personal index finger. Silences of the complicated. Imaginative finds.

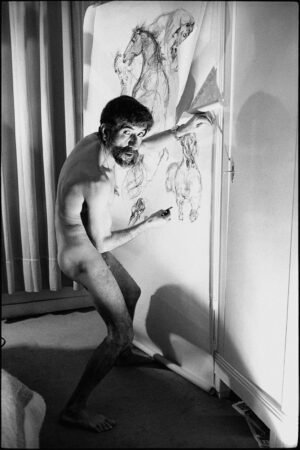

Like this “Self-portrait with C-gasoline”, in which the photographer, as a deliberate arsonist, takes the stage and pays for it with his own life. The price might have been exorbitant, but in the end it’s less a portrait of gasoline than a portrait of an essence, an ontology, a way of being, a thief of fire, warm, ignited, a risk-taker, yet not a nutcase. This running flame is Prometheus in miniature, unleashed not on his rock at the ends of the earth, but in the Val d’Oise, on the edge of cartoonist Siné’s fire-extinguisher pool.

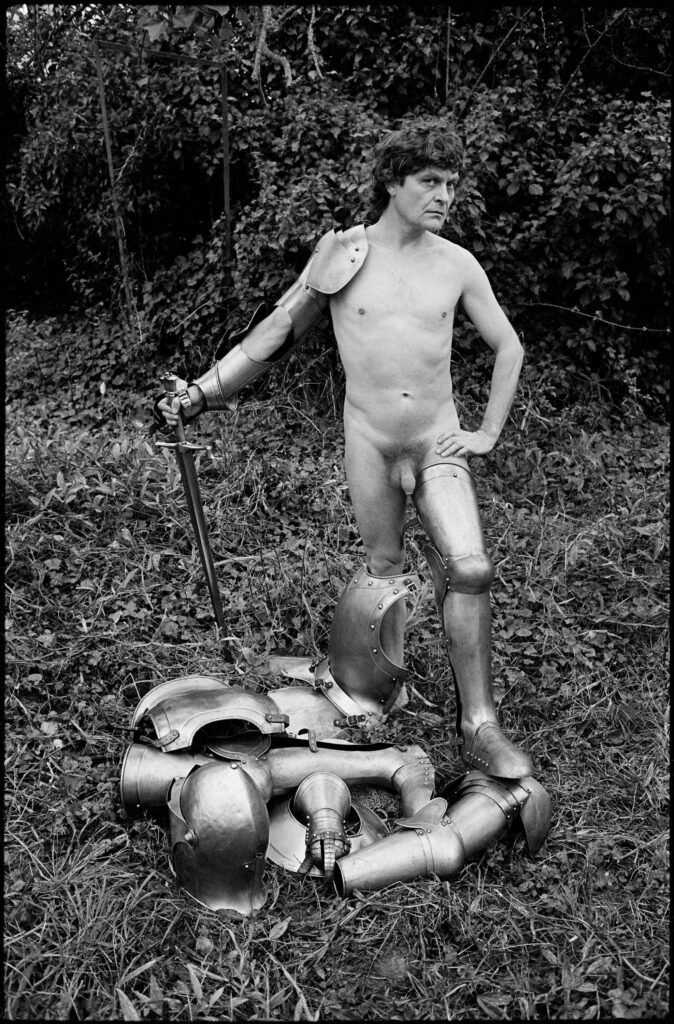

Baumann, referring to his portrait of elderly Philippe Soupault, overloaded with ninety-two years of memories and as if appalled, he the surrealist, to have spent an entire existence in a reality that is eventually nothing but smoke: “Undressing can also mean showing one’s wrinkles, the passing of time. To be able to accept death (…) A portrait is successful, I think, when it reaches that dimension. Nakedness.

The question is: THE EXPOSURE OF WHAT EXACTLY?

The answer comes from Jean Paulhan: “People gain from being known. They gain in mystery. That’s the great thing about human beings: if you happen to discover the mystery they are at first, you’re bound to discover the enigma they are afterwards. So, who’s who?

And what is Iconic Portraits, if not a concentration and pileup of revealing rebus, like any true portrait exhibition? But an invigorating concentration and pileup, because if no exhibition or book of the living has ever been so lively, no exhibition or book of the dead has ever been so cheerful, restless, motley, variable, energetic, offbeat, whimsical and inventive.

Michel Wichegrod 2024